Yesterday's Gospel is one of my all-time favorite parables, that of the laborers in the vineyard. The story is simple --- deceptively so in fact: workers come to work in the vineyard at various parts of the day all having contracted with the master of the vineyard to work for a day's wages. Some therefore work the whole day, some are brought in to work only half a day, and some are hired only when the master comes for them at the end of the day. When time comes to pay everyone what they are owed those who came in to work last are paid first and receive a full day's wages. Those who came in to work first expect to be paid more than these, but are disappointed and begin complaining when they are given the same wage as those paid first. The response of the master reminds them that he has paid them what they contracted for, nothing less, and then asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own money. A saying is added: [in the Kingdom of God] the first shall be last and the last first.

Now, it is important to remember what the word parable means in appreciating what Jesus is actually doing with this story and seeing how it challenges us today. The word parable, as I have written before, comes from two Greek words, para meaning alongside of and balein, meaning to throw down. What Jesus does is to throw down first one set of values -- one well-understood or common-perspective --- and allow people to get comfortable with that. (It is one they understand best so often Jesus merely needs to suggest it while his hearers fill in the rest. For instance he mentions a sower, or a vineyard and people fill in the details. Today he might well speak of a a CEO in an office, or a mother on a run to pick up kids from a swim meet or soccer practice.) Then, he throws down a second set of values or a second way of seeing reality which disorients and gets his hearers off-balance. This second set of values or new perspective is that of the Kingdom of God. Those who listen have to make a decision. (The purpose of the parable is not only to present the choice, but to engage the reader/hearer and shake them up or disorient them a bit so that a choice for something new can (and hopefully will) be made.) Either Jesus' hearers will reaffirm the common values or perspective or they will choose the values and perspective of the Kingdom of God. The second perspective, that of the Kingdom is often counterintuitive, ostensibly foolish or offensive, and never a matter of "common sense". To choose it --- and therefore to choose Jesus and the God he reveals --- ordinarily puts one in a place which is countercultural and often apparently ridiculous.

So what happens in yesterday's Gospel? Again, Jesus tells a story about a vineyard and a master hiring workers. His readers know this world well and despite Jesus stating specifically that each man hired contracts for the same wage, common sense says that is unfair and the master MUST pay the later workers less than he pays those who came early to the fields and worked through the heat of the noonday sun. And of course, this is precisely what the early workers complain about to the master. It is precisely what most of US would complain about in our own workplaces if someone hired after us got more money, for instance, or if someone with a high school diploma got the same pay and benefit package as someone with a doctorate --- never mind that we agreed to this package! The same is true in terms of religion: "I spent my WHOLE life serving the Lord. I was baptized as an infant and went to Catholic schools from grade school through college and this upstart convert who has never done anything at all at the parish gets the Pastoral Associate job? No Way!! No FAIR!!" From our everyday perspective this would be a cogent objection and Jesus' insistence that all receive the same wage, not to mention that he seems to rub it in by calling the last hired to be paid first (i.e., the normal order of the Kingdom), is simply shocking.

And yet the master brings up two points which turn everything around: 1) he has paid everyone exactly what they contracted for --- a point which stops the complaints for the time being, and 2) he asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own gifts or money. He then reminds his hearers that the first shall be last, and the last first in the Kingdom of God. If someone was making these remarks to you in response to cries of "unfair" it would bring you up short, wouldn't it? If you were already a bit disoriented by a pay master who changed the rules of commonsense this would no doubt underscore the situation. It might also cause you to take a long look at yourself and the values by which you live your life. You might ask yourself if the values and standards of the Kingdom are really SO different than those you operate by everyday of your life, not to mention, do you really want to "buy into" this Kingdom if the rewards are really parcelled out in this way, even for people less "gifted" and less "committed" than you consider yourself! Of course, you might not phrase things so bluntly. If you are honest, you will begin to see more than your own brilliance, giftedness, or commitedness; You might begin to see these along with a deep neediness, a persistent and genuine fear at the cost involved in accepting this "Kingdom" instead of the world you know and have accommodated yourself to so well.

You might consider too, and carefully, that the Kingdom is not an otherwordly heaven, but that it is the realm of God's sovereignty which, especially in Christ, interpenetrates this world, and is actually the goal and perfection of this world; when you do, the dilemma before you gets even sharper. There is no real room for opting for this world's values now in the hope that those "other Kingdomly values" only kick in after death! All that render to Caesar stuff is actually a bit of a joke if we think we can divvy things up neatly and comfortably (I am sure Jesus was asking for the gift of one's whole self and nothing less when he made this statement!), because after all, what REALLY belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God? No, no compromises are really allowed with today's parable, no easy blending of the vast discrepancy between the realm of God's sovereignty and the world which is ordered to greed, competition, self-aggrandizement and hypocrisy, nor therefore, to the choice Jesus puts before us.

So, what side will we come down on after all this disorientation and shaking up? I know that every time I hear this parable it touches a place in me (yet another one!!) that resents the values and standards of the Kingdom and that desires I measure things VERY differently indeed. It may be a part of me that resists the idea that everything I have and am is God's gift, even if I worked hard in cooperating with that (my very capacity and willingness to cooperate are ALSO gifts of God!). It may be a part of me that looks down my nose at this person or that and considers myself better in some way (smarter, more gifted, a harder worker, stronger, more faithful, born to a better class of parents, etc, etc). It may be part of me that resents another's wage or benefits despite the fact that I am not really in need of more myself. It may even be a part of me that resents my own weakness and inabilities, my own illness and incapacities which lead me to despise the preciousness and value of my life and his own way of valuing it which is God's gift to me and to the world. I am socialized in this first-world-culture and there is no doubt that it resides deeply and pervasively within me contending always for the Kingdom of God's sovereignty in my heart and living. I suspect this is true for most of us, and that today's Gospel challenges us to make a renewed choice for the Kingdom in yet another way or to another more profound or extensive degree.

For Christians every day is gift and we are given precisely what we need to live fully and with real integrity if only we will choose to accept it. We are precious to God, and this is often hard to really accept, but neither more nor less precious than the person standing in the grocery store line ahead of us or folded dirty and disheveled behind a begging sign on the street corner near our bank or outside our favorite coffee shop. The wage we have agreed to (or been offered) is the gift of God's very self along with his judgment that we are indeed precious, and so, the free and abundant but cruciform life of a shared history and destiny with that same God whose characteristic way of being is kenotic. He pours himself out with equal abandon for each of us whether we have served him our whole lives or only just met him this afternoon. He does so whether we are well and whole, or broken and feeble. And he asks us to do the same, to pour ourselves out similarly both for his own sake and for the sake of his creation-made-to-be God's Kingdom.

To do so means to decide for his reign now and tomorrow and the day after that; it means to accept his gift of Self as fully as he wills to give it, and it therefore means to listen to him and his Word so that we MAY be able to decide and order our lives appropriately in his gratuitous love and mercy. The parable in today's Gospel is a gift which makes this possible --- if only we would allow it to work as Jesus empowers and wills it!

25 September 2017

Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard (reprise)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:31 PM

![]()

![]()

15 September 2017

Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows (Our Lady of Compassion)

I think it is sometimes difficult for us to allow Mary to truly accompany us in our struggles. That is because we Catholics have the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception the affirmation that somehow, through the merits of Christ's own death and resurrection, Mary was preserved from the state of original sin and sometimes it has been suggested that she cannot, therefore, suffer. It is important to understand however, that theologians recognize four forms of suffering which are inherent in human life even apart from any situation of estrangement and alienation from God. Every one of us experiences these forms of suffering because they are part and parcel of human existence. They are necessary if we are to grow to maturity in our truest vocations, namely being authentically human with and from God. The Scriptures tell us Jesus grew in grace and stature; Mary did the same and shows us what it means not only to be a Woman of Sorrows but also a woman of great faith, hope, and compassion (this feast was originally named after Mary as Our Lady of Compassion). As such she is a model of our own vocations and one whom we trust to be with us in every difficulty.

I think it is sometimes difficult for us to allow Mary to truly accompany us in our struggles. That is because we Catholics have the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception the affirmation that somehow, through the merits of Christ's own death and resurrection, Mary was preserved from the state of original sin and sometimes it has been suggested that she cannot, therefore, suffer. It is important to understand however, that theologians recognize four forms of suffering which are inherent in human life even apart from any situation of estrangement and alienation from God. Every one of us experiences these forms of suffering because they are part and parcel of human existence. They are necessary if we are to grow to maturity in our truest vocations, namely being authentically human with and from God. The Scriptures tell us Jesus grew in grace and stature; Mary did the same and shows us what it means not only to be a Woman of Sorrows but also a woman of great faith, hope, and compassion (this feast was originally named after Mary as Our Lady of Compassion). As such she is a model of our own vocations and one whom we trust to be with us in every difficulty.

The four forms of suffering which exist apart from any state of sin are 1) aloneness or loneliness, 2) limits, 3) anxiety, and 4) temptation. It is possible to look at the Creation and Garden of Eden narratives in Genesis and find each of these present before any sin enters the picture; again, they are necessary if we are to grow in grace and stature. Aloneness is necessary if we are to be moved to fellowship, to community or union with others. As Douglas John Hall** comments. [[love presupposes the element and experience of separation]] or again, [[Thus, loneliness which is certainly a cause of much human suffering, is at the same time a kind of prerequisite of what Paul in 1 Corinthians 13 names the "greatest" of all creaturely capacities, the capacity of love.]] The experience of limits is necessary if we are to experience transcendence or the reality of being gifted. Without limits we could not dream; we could not experience wonder, surprise, or gratitude. Anything and everything at anytime would be the rule and we neither would nor could significantly develop the capacity for self-control or sacrifice under such a rule. Everything would be ours; we would have a right to anything at anytime. Nothing would ever truly be a gift to us. We would never learn to prioritize our desires or needs, nor would there be any need to work towards something, share with others, or sacrifice our own needs for the needs of the other. Growth and transcendence as well as generosity and selflessness presuppose the experience of limits and though this experience causes us suffering, it is inherent in human life.

The third form of suffering which is similarly inherent even apart from sin is temptation. Since our humanity is a task set before us, something we must achieve in the decisions we take and the choices we make --- most particularly in the choices we make for God, for the good, loving, and true, we will also be faced constantly by alternative realities and the possibility of choosing other than that which is worthy of us. We create the persons we are called to be precisely by meeting the reality of temptation, discerning what calls us to greater wholeness and holiness, and choosing this reality. Our capacity for morality makes temptation necessary. Our capacity for freedom does the same. We must know temptation if we are to grow more deeply rooted in the God who calls us to love freely. Temptation is the presupposition for achieving integrity and even nobility as human persons. Temptation is clearly present in the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis. Adam and Eve are told, "You may eat of every tree in the garden EXCEPT the tree of knowledge of good and evil (note the imposition of limits and the possibility of choices here)." And Eve is tempted. Her long dialogue with the serpent (an externalization of what she is thinking here) is thus an externalization of her temptation to do other than God wills; in fact this dialogue or bit of theologizing is a paradigm of what temptation looks like for us!

The third form of suffering which is similarly inherent even apart from sin is temptation. Since our humanity is a task set before us, something we must achieve in the decisions we take and the choices we make --- most particularly in the choices we make for God, for the good, loving, and true, we will also be faced constantly by alternative realities and the possibility of choosing other than that which is worthy of us. We create the persons we are called to be precisely by meeting the reality of temptation, discerning what calls us to greater wholeness and holiness, and choosing this reality. Our capacity for morality makes temptation necessary. Our capacity for freedom does the same. We must know temptation if we are to grow more deeply rooted in the God who calls us to love freely. Temptation is the presupposition for achieving integrity and even nobility as human persons. Temptation is clearly present in the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis. Adam and Eve are told, "You may eat of every tree in the garden EXCEPT the tree of knowledge of good and evil (note the imposition of limits and the possibility of choices here)." And Eve is tempted. Her long dialogue with the serpent (an externalization of what she is thinking here) is thus an externalization of her temptation to do other than God wills; in fact this dialogue or bit of theologizing is a paradigm of what temptation looks like for us!

The fourth form of suffering inherent in the human life even apart from original sin is anxiety. At every moment we are threatened by death in all of its degrees and forms.**** We are threatened by non-being. Our capacity to act courageously and affirm life and God in the face of this threat; to choose these rather than other lesser (less ultimate), more immediate, and less mysterious forms of security, matures as we embrace our anxiety and trust the promises of God instead. To become people of genuine hope means to take on the threat of non-being, to believe in the God that is Being-itself and embrace more and more completely the Gospel in which sin and death are defeated precisely in weakness and kenosis (self-emptying). Today's readings, but especially the responsorial psalm, make clear the transcendence and ultimate security that comes only from affirming (trusting in) God in the face of death: [[I bless the LORD who counsels me; even in the night my heart exhorts me. I set the LORD ever before me; with him at my right hand I shall not be disturbed. R. You are my inheritance, O Lord. You will show me the path to life, fullness of joys in your presence, the delights at your right hand forever.]] Like temptation, anxiety in the face of death in all of its degrees and forms is essential if we are to grow as human beings who live in dialogue with God and look to Him for the peace nothing and no one else can give.

Mary, Our Lady of Compassion and also Our Lady of Sorrows knew all of these forms of suffering very well. If you look at the seven sorrows which marked her life it is easy to distinguish these forms. Mary knew genuine courage, had pondered in her heart the will of God which grounded her courage, and again and again chose to trust (him) who "brings good out of all things for those who believe". In every situation in spite of terror and pain and even personal "inadequacy" in the face of Sinful existence, Mary chooses to hang onto the God who promises to redeem all of reality by bringing it to fulfillment within himself. In other words, time and again Mary says yes to an ongoing, constant dialogue with God as she embraced the task of becoming fully human. She does indeed grow in grace and stature to become the one we identify as a paradigm of authentically human faith, courage, hope, and compassion. Thanks be to God!

Mary, Our Lady of Compassion and also Our Lady of Sorrows knew all of these forms of suffering very well. If you look at the seven sorrows which marked her life it is easy to distinguish these forms. Mary knew genuine courage, had pondered in her heart the will of God which grounded her courage, and again and again chose to trust (him) who "brings good out of all things for those who believe". In every situation in spite of terror and pain and even personal "inadequacy" in the face of Sinful existence, Mary chooses to hang onto the God who promises to redeem all of reality by bringing it to fulfillment within himself. In other words, time and again Mary says yes to an ongoing, constant dialogue with God as she embraced the task of becoming fully human. She does indeed grow in grace and stature to become the one we identify as a paradigm of authentically human faith, courage, hope, and compassion. Thanks be to God!

_____________________________________________________

** Hall, Douglas John, God and Human Suffering I cannot recommend this book by Douglas John Hall more highly. Hall's work is generally focused on the Theology of the Cross, especially as it takes shape in a Northern American context. I first read this maybe 30 years ago and have reread it several times. It is a fine introduction to the nature and theology of suffering and a call to become people who can suffer with courage and faith.

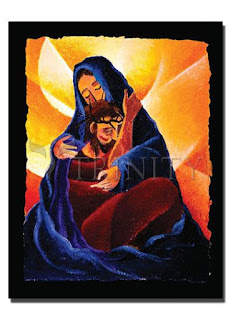

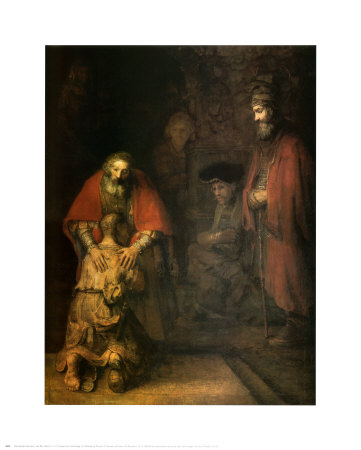

***The painting at the top of the post is Brother Mickey McGrath's Madonna of the Holocaust. I used this painting today in a service I did for the parish as part of my reflection on the feast and readings. The second illustration is Mickey's painting of the fourth station of the cross and one of the seven sorrows. I love this image. Mary is mountain-like and immovable in faith and compassion. She is wounded by the same crown that encircles and pierces her Son's head, yet she consoles him. Jesus rests in her lap for the moment and the moment seems timeless. Jesus holds onto her as she hangs onto God and God's promises, tightly, desperately, in both peace, and terrible pain. Both paintings are perfect images for this feast of Our Lady of Sorrows/Compassion and are available in various forms and sizes from Trinity Stores.

**** While we are threatened by death in all of it's forms and degrees, the form and degree of death uniquely associated with sinful existence is "godless death" --- also known as eternal death or second death. It is death in which one is eternally separated from God and the life of God. Mary knew anxiety because she was threatened by natural (not sinful) death, a natural and transitional form of perishing.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:55 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Our Lady of Compassion, Our Lady of Sorrows, suffering- natural forms

14 September 2017

Feast of the Exaltation (Triumph) of the Cross (Reprise)

[[Dear Sister Laurel, Could you write something about [today's] feast of the Exaltation of the Cross? What is a truly healthy and yet deeply spiritual way to exalt the Cross in our personal lives, and in the world at large (that is, supporting those bearing their crosses while not supporting the evil that often causes the destruction and pain that our brothers and sisters are called to endure due to sinful social structures?]]

The above question which arrived by email was the result of reading some of my posts, mainly those on victim soul theology, the Pauline theology of the Cross, and some earlier ones having to do with the permissive will of God. For that reason my answer presupposes much of what I wrote in those and I will try not to be too repetitive. First of all, in answering the question, I think it is helpful to remember the alternative name of this feast, namely, the Triumph of the Cross. For me personally this is a "better" name, and yet, it is a deeply paradoxical one, just like its alternative.

(Crucifix in Ambo of Cathedral of Christ the Light; Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, or Cathedral Sunday in the Diocese of Oakland)

How many times have we heard it suggested that Christians ought not wear crosses around their necks as jewelry any more than they should wear tiny images of electric chairs, medieval racks or other symbols of torture and death? Similarly, how many times has it been said that making jewelry of the cross trivializes what happened there? There is a great deal of truth in these objections, and in similar ones! On the one hand the cross points to the slaughter by torture of hundreds of thousands of people by an oppressive state. More individually it points to the slaughter by torture of an innocent man in order to appease a rowdy religious crowd by an individual of troubled but dishonest conscience, one who put "the supposed greater good" before the innocence of this single victim.

And of course there were collaborators in this slaughter: the religious establishment, disciples who were either too cowardly to stand up for their beliefs, or those who actively betrayed this man who had loved them and called them to a life of greater abundance (and personal risk) than they had ever known before. If we are going to appreciate the triumph of the cross, if we are going to exalt it as Christians do and should, then we cannot forget this aspect of it. Especially we cannot forget that much that happened here was not the will of God, nor that generally the perpetrators were not cooperating with that will! The cross was the triumph of God over sin and sinful godless death, but it was also a sinful and godless human (and societal!) act of murder by torture. (In fact one could argue it was a true divine triumph only because it was also these all-too-human things.) Both aspects exist in tension with each other, as they do in all of God's victories in our world. It is this tension our jewelry and other crucifixes embody: they are miniature instruments of torture, yes, but also symbols of God's ultimate triumph over the powers of sin and death with which humans are so intimately entangled and complicit.

In our own lives there are crosses, burdens which are the result of societal and personal sin which we must bear responsibly and creatively. That means not only that we cannot shirk them, but also that we bear them with all the asistance that God puts into our hands. Especially it means allowing God to assist us in the carrying of this cross. To really exalt the cross of Christ is to honor all that God did with and made of the very worst that human beings could do to another human being. To exult in our own personal crosses means, at the very least, to allow God to transform them with his presence. That is the way we truly exalt the Cross: we allow it to become the way in which God enters our lives, the passion that breaks us open, makes us completely vulnerable, and urges us to embrace or let God embrace us in a way which comforts, sustains, and even transfigures the whole face of our lives.

If we are able to do this, then the Cross does indeed triumph. Suffering does not. Pain does not. Neither will our lives be defined in terms of these things despite their very real presence. What I think needs to be especially clear is that the exaltation of the cross has to do with what was made possible in light of the combination of awful and humanly engineered torment, and the grace of God. Sin abounded but grace abounded all the more. Does this mean we invite suffering so that "grace may abound all the more?" Well, Paul's clear answer to that question was, "By no means!" How about tolerating suffering when we can do something about it? What about remaining in an abusive relationship, or refusing medical treatment which would ease mental and physical pain, for instance? Do we treat these as crosses we must bear? Do we allow ourselves to become complicit in the abuse or the destructive effects of pain and physical or mental illness? I think the general answer is no, of course not.

That means we must look for ways to allow God's grace to triumph, while the triumph of grace always results in greater human freedom and authentic functioning. Discerning what is necessary and what will really be an exaltation of the cross in our own lives means determining and acting on the ways freedom from bondage and more authentic humanity can be achieved. Ordinarily this will mean medical treatment; or it will mean moving out of the abusive situation. In all cases it means remaining open to and dependent upon God and to what he desires for our lives in spite of the limitations and suffering inherent in them. This is what Jesus did, and what made his cross salvific. This openness and responsiveness to God and what he will do with our lives is, as I have said many times before, what the Scriptures called obedience. Let me be clear: the will of God in any situation is that we remain open to him and that authentic humanity be achieved. We must do whatever it is that allows us to not close off to God, and to remain open to growth as human. If our pain dehumanizes, then we must act in ways which changes that. If our lives cease to reflect the grace of God (and this means fails to be a joyfilled, free, fruitful, loving, genuinely human life) then we must act in ways which changes that.

The same is true in society more generally. We must act in ways which open others to the grace of God. Yes, suffering does this, but this hardly means we simply tell people to pray, grin, and bear it ---- much less allow the oppressive structures to stay in place! As the gospels tell us, "the poor you will always have with you" but this hardly means doing nothing to relieve poverty! Similarly we will always have suffering with us on this side of death, and especially the suffering that comes when human beings institutionalize their own sinful drives and actions. What is essential is that the Cross of Christ is exalted, that the Cross of Christ triumphs in our lives and society, not simply that individual crosses remain or that we exalt them (especially when they are the result of human engineering and sin)! And, as I have written before, to allow Christ's Cross to triumph is to allow the grace of God to transform all the dark and meaningless places with his presence, light and love. It is ONLY in this way that we truly "make up for what is lacking in the passion of Christ."

The paradox in today's feast is that the exaltation of the Cross implies suffering, and stresses that the cross empowers the ability to suffer well, but at the same time points to a freedom the world cannot grant --- a freedom in which we both transcend and transform suffering because of a victory Christ has won over the powers of sin and death which are built right into our lives and in the structures of this world. Thus, we cannot ever collude with the powers of this world; we must always be sure we are acting in complicity with the grace of God instead. Sometimes this means accepting the suffering that comes our way (or encouraging and supporting others in doing so of course), but never for its own sake. If our (or their) suffering does not result in greater human authenticity, greater freedom from bondage, greater joy and true peace, then it is not suffering which exalts the Cross of Christ. If it does not in some way transform and subvert the structures of this world which oppress and destroy, then it does not express the triumph of Jesus' Cross, nor are we really participating in that Cross in embracing our own.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:39 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, paradox, Theology of the Cross

10 September 2017

Treat Them Like Gentiles and Tax Collectors (Reprised)

In today's Gospel pericope we hear Jesus telling folks to speak to those who have offended against God one on one and then, if that is ineffective, bring in two more brothers or sisters to talk with the person, and then, if that too is ineffective, to bring matters to the whole community --- again so the offended can be brought back into what we might call "full communion". If even that is ineffective then we are told to treat the person(s) as we treat Gentiles and tax collectors. In every homily I have ever heard about this passage this final dramatic command has been treated as justification for excommunication. Even today our homilist referred to excommunication --- though, significantly, he stressed the medicinal and loving motive for such a dire step. The entire passage is read as a logical, common-sense escalation and intervention: start one on one, try all you can, bring others in as needed, and if that doesn't work (that is, if the person remains recalcitrant) then wash your hands of him or, if stressing the medicinal nature of the act, separate yourselves from him until he comes to his senses and repents! In this reading of the text Matthew is giving us the Scriptural warrant for "tough love."

In today's Gospel pericope we hear Jesus telling folks to speak to those who have offended against God one on one and then, if that is ineffective, bring in two more brothers or sisters to talk with the person, and then, if that too is ineffective, to bring matters to the whole community --- again so the offended can be brought back into what we might call "full communion". If even that is ineffective then we are told to treat the person(s) as we treat Gentiles and tax collectors. In every homily I have ever heard about this passage this final dramatic command has been treated as justification for excommunication. Even today our homilist referred to excommunication --- though, significantly, he stressed the medicinal and loving motive for such a dire step. The entire passage is read as a logical, common-sense escalation and intervention: start one on one, try all you can, bring others in as needed, and if that doesn't work (that is, if the person remains recalcitrant) then wash your hands of him or, if stressing the medicinal nature of the act, separate yourselves from him until he comes to his senses and repents! In this reading of the text Matthew is giving us the Scriptural warrant for "tough love."

But I was struck by a very different reading during my hearing of the Gospel this morning. We think of Jesus turning things on their heads so very often in what he says; more we think about how often he turns things on their head by what he does. With this in mind the question which first occurred to me was, "But what would this have meant in Jesus' day for disciples of this man from Nazareth, not what would it have meant for hundreds of years of Catholic Christianity!? Is the logic of this reading different, even antithetical to the logical, commonsense escalation outlined above?" And the answer I "heard" was, "Of course it is different! I am asking you to escalate your attempts to bring this person home, not to wash your hands of her. To do that I am suggesting you treat her as you might someone for whom the Gospel is a foreign word now -- someone who needs to hear it as much or more than you ever did yourself." Later I thought in a kind of jumble, "That means to treat her with even greater gentleness and care, even greater love and a different kind of intimacy. Her offense has effectively put her outside the faith community. Jesus is asking that we let ourselves be the "outsider" who stands with her where she is. He is saying we must try to speak in a language she will truly hear. Make of her a neighbor again; meet her in the far place, learn her truth before we try to teach her "ours". After all, what I and others have said thus far has either not been understood or it was not compelling for her."

While I should not have been surprised, I admit I was startled by my initial thoughts! Of course I knew that Jesus associated with tax collectors and with Gentiles. The reading with the Canaanite women last week or the week before makes it clear that Jesus even changed his mind about his own mission in light of the faith he found among Gentiles. Meanwhile, today's reading is taken from a Gospel attributed to Matthew, an Apostle who is identified as a tax collector! Shouldn't we be holding onto our seats in some anticipation while listening for Jesus – as he always does -- to say something that turns conventional wisdom and our entire ecclesiastical and spiritual world on its head? Maybe my thoughts were not really so crazy after all and maybe those homilies I have heard for years have NOT had it right! So I looked again at the Gospel lection from today in its Matthean context. It is sandwiched between passages about humbling ourselves as children (those with no status), not being a source of stumbling and estrangement to others, searching for the one sheep that has gone astray even if it means leaving behind the 99 who have not strayed, and Peter asking how often he should forgive his brother to which Jesus says seven times seventy!

While I should not have been surprised, I admit I was startled by my initial thoughts! Of course I knew that Jesus associated with tax collectors and with Gentiles. The reading with the Canaanite women last week or the week before makes it clear that Jesus even changed his mind about his own mission in light of the faith he found among Gentiles. Meanwhile, today's reading is taken from a Gospel attributed to Matthew, an Apostle who is identified as a tax collector! Shouldn't we be holding onto our seats in some anticipation while listening for Jesus – as he always does -- to say something that turns conventional wisdom and our entire ecclesiastical and spiritual world on its head? Maybe my thoughts were not really so crazy after all and maybe those homilies I have heard for years have NOT had it right! So I looked again at the Gospel lection from today in its Matthean context. It is sandwiched between passages about humbling ourselves as children (those with no status), not being a source of stumbling and estrangement to others, searching for the one sheep that has gone astray even if it means leaving behind the 99 who have not strayed, and Peter asking how often he should forgive his brother to which Jesus says seven times seventy!

I think Jesus is reminding us of the difference between a community which is united in and motivated by Christ's own love (a very messy business sometimes) and one which is united in and mainly concerned with discipline (not so messy, but not so fruitful or inspired either). I think too he is reminding us of a Church which is always a missionary Church, always going out to others, always seeking to reconcile the entire world in the power of the Gospel. It is not a fortress which protects its precious patrimony by shutting itself off from those who do not believe, letting them fend for themselves or simply find their own ways to the baptistry or confessional doors; instead it achieves its mission by extending its love, its Word, and even its Sacraments to those who most need them --- the alien and alienated. It is a Church that really believes we hold things as sacred best when we give them away (which is NOT the same thing as giving them up!). Meanwhile Jesus may also be saying, "If your brother or sister has not and will not hear you, perhaps you have not loved them well or effectively enough; find a new way, even a more costly way. After all, my way (the Way I am!) is not the way of conventional wisdom, it is the scandalous, foolish, and sacrificial way of the Kingdom of God!

I had always thought today's reading a "hard one" because it seemed to sanction the excommunication of brothers and sisters in Christ. But now I think it is a hard one for an entirely different reason. It gives us a Church where no one can truly be at home so long as we are not reaching out to those who have not heard the Gospel we have been entrusted with proclaiming. It is a Church of open doors and open table fellowship (open commensality) because it is a church of open and missionary hearts -- just as God's own heart, God's own essential nature, is missionary. Above all it is a church where those who truly belong are the ones who really do not belong anywhere else! We proclaim a Gospel in which we who belong to Christ through baptism are the last and those outside our communion are first and, at least potentially, the Apostles on which the Church is built.

When we treat people like Gentiles and tax collectors we treat them in exactly this way, namely, as those whose truest home is around the table with us, listening to and celebrating the Word with us, ministering to and with us as at least potential brothers and sisters in Christ! We treat them as Gentiles and tax collectors when we take the time to enter their world so that we can speak to them in a way they can truly hear, when we love them (are brothers and sisters to them) as they truly need, not only as we are comfortable doing in our own cultures and families. Paul, after all, spoke of becoming and being all things to all persons --- just as God became man for us. He was not speaking of indifferentism or saying with our lives that Christ doesn't really matter; just the opposite in fact. He was telling us we must be Christians in this truly startling way --- persons who can and do proclaim the Gospel of a crucified and risen Christ wherever we go because we let ourselves be at home and among (potential) brothers and sisters wherever we go. We do as God did for us in Christ; we let go of the prerogatives which are ours and travel to the far place in any and all the ways we need to in order to fulfill the mission of our God to truly be all in all.

When the logic, drama, and tension of today's Gospel lection escalate it is to this conclusion, I think, not to a facile justification of excommunication. In this pericope Jesus does not ask us to progressively enlist more people to increase the force with which we strong arm those who have become alienated, much less to support us as we cut them loose if they are unconvinced and unconverted, but to offer them richer, more diverse and extensive chances to be heard and to hear --- increasing opportunities, that is, to be empowered to change their minds and hearts when we, acting alone, have failed them in this way. This is what it means to forgive; it is what it means to be commissioned as an Apostle of Christ. And if that sounds naïve, imprudent, impractical, and even impossible, I suspect Jesus' original hearers felt the same about the pericopes which form this lection's immediate context: becoming as children with no status except that given them by God, leaving the 99 to seek the single lost sheep or forgiving what is effectively a countless number of times. Certainly that's how someone writing under the name of a tax collector-turned-Apostle presents the matter.

When the logic, drama, and tension of today's Gospel lection escalate it is to this conclusion, I think, not to a facile justification of excommunication. In this pericope Jesus does not ask us to progressively enlist more people to increase the force with which we strong arm those who have become alienated, much less to support us as we cut them loose if they are unconvinced and unconverted, but to offer them richer, more diverse and extensive chances to be heard and to hear --- increasing opportunities, that is, to be empowered to change their minds and hearts when we, acting alone, have failed them in this way. This is what it means to forgive; it is what it means to be commissioned as an Apostle of Christ. And if that sounds naïve, imprudent, impractical, and even impossible, I suspect Jesus' original hearers felt the same about the pericopes which form this lection's immediate context: becoming as children with no status except that given them by God, leaving the 99 to seek the single lost sheep or forgiving what is effectively a countless number of times. Certainly that's how someone writing under the name of a tax collector-turned-Apostle presents the matter.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:22 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Gentiles and Tax Collectors

04 September 2017

God Alone is Enough (Reprise)

Because of recent posts and the phrase "God alone is enough" which I have used therein, I have been asked if this isn't misanthropic, anti-Christian, or downright isolationist --- all things I often and consistently write against. In Lent 2012 I posted the following piece which describes the meaning of this difficult affirmation. An added section (italicized) is included on the place of friendship and other significant relationships which, I hope, clarifies some of the brief comments in the original piece.

[[Hi Sister! What does it mean to say that God alone is enough? I need my family and friends and I wouldn't be the person I am without them. Does saying God Alone is Enough mean that we don't need others? Does it mean something different for you as a hermit than for me as a single teacher?]]

[[Hi Sister! What does it mean to say that God alone is enough? I need my family and friends and I wouldn't be the person I am without them. Does saying God Alone is Enough mean that we don't need others? Does it mean something different for you as a hermit than for me as a single teacher?]]

Wonderful questions! The phrase God Alone is Enough is an ambiguous one, meaning it has different and overlapping meanings which can also be misunderstood. So, for instance, the word "enough" can either basically mean we don't need anyone or anything else in our lives, or it can mean that God is the one reality which answers every fundamental or foundational need and completes us as persons. For most persons, the truth is that in adulthood we do not come to human wholeness apart from our relationships with other people and so it is ordinarily the case that the affirmation God alone is enough refers to the second sense: only God is sufficient to truly complete us, to empower us to the transcendence of genuine humanity, to serve as the source and ground of being and meaning in our lives.

This is especially true when one asks what the word "alone" means. Does it mean the person needs no one and nothing else besides God? Does it mean one can go one's own way motivated merely by individualism (what monastic life critically refers to as singularitas) and even a form of narcissism? Does it mean that one can dismiss the world around them as unworthy of their spirituality and live a kind of falsely "spiritualized" isolation? Or, again, does it mean that only God can answer every human need and complete us as persons? In every case, that is, for every person [whether hermit or not] it means the latter. For most people their reliance on God as the foundation of their lives will actually lead to more -- and more healthy -- personal relationships, not to fewer much less to less healthy ones. Only in the case of hermits or anchorites does it mean that the hermit relies on God alone to the significant and lifelong limitation or relative exclusion of human relationships. We do this not only because we are called to do it for ourselves and for God who desires and wills our love, but again because it witnesses in a rather vivid way to that foundational relationship which stands at the core of every person.

So yes, my sense of the meaning of this phrase may be different than yours in some ways. The two senses I have spoken of also overlap to a significant degree though. By the way, as we approach Holy Week it is important to note that the church will be looking at a related way in which "God alone is enough." What we will hear proclaimed is the fact that only God can overcome sin and death: only God is that love which is stronger than death, only God is generous enough to empty himself completely and become subject to the powers and principalities of our world so that they might also be defeated. I will write about that a bit more though in the next weeks.

[Please note, when I spoke above of the relative exclusion of human relationships I really mean the accent to be on [the word] relative. Hermits are not misanthropes but at the same time they limit contact with others for the sake of the witness they are called to regarding the foundational place of God in every human life. Hermits, at least in my experience, because again they are not usually recluses or ordinarily called to reclusion, must cultivate some few but quality relationships --- friends, directors, and those who accompany them in more "professional" or formal ways --- not only because there are real limits on the number of relationships in which the hermit can actually participate if their solitude is to be real, but because at the same time one's physical solitude requires such significant, even "sacramental," relationships if it is to be the rich and nourishing environment of the heart hermits require and commit to in the name of the Church.

It is hard to describe this paradox but it is linked to the distinction between being merely alone and living the silence of solitude. Consider that the ecclesial nature of this vocation provides a communal context for all authentic eremitical solitude; within this ecclesial context there will be the sustaining warmth, love, challenge, discipline, and consolation of the kinds of relationships I mentioned above --- limited though these will necessarily be. Each will mediate the presence and will of God in ways which supplement the way God comes to us in physical solitude and solitary prayer. Each will help shape the human heart in ways which allow it to embrace God fully -- and be more fully embraced by him -- in the rigors of solitude. They will thus also help the hermit maintain her commitment to all dimensions of the truth that "God alone is enough" for us --- but (and this is the sharpest form of the paradox) especially the solitary dimension she has freely embraced and is publicly responsible for.]

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:57 PM

![]()

![]()

A Contemplative Moment: On Pilgrimage and Finding Ourselves

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

8:14 PM

![]()

![]()

Developing the Heart of a Hermit (Reprise)

I was asked about the creation of the hermit heart recently and someone else asked what it means to have the heart of a hermit. Thus, I am going to repost something I wrote about 14-15 months ago because I don't think I can improve on it at this point.

I was asked about the creation of the hermit heart recently and someone else asked what it means to have the heart of a hermit. Thus, I am going to repost something I wrote about 14-15 months ago because I don't think I can improve on it at this point.

[[Hi Sister, when you write about having the heart of a hermit and moving from isolation to solitude do you mean that someone comes to this through some form of trauma or serious personal wounding and alienation? Is this necessary? Can a person who has never been hurt or broken develop the "heart of a hermit"?]]

When I speak of a desert I mean the literal wilder-nesses we know as deserts (the Thebaid, Scetes, Mojave, Sonoran, Sahara, etc), but I also mean any extended situation which demands or forces a person to plumb the depths of their own personal resources --- courage, intelligence, creativity, sense of security, personal gifts and talents, sense of self, faith, hope, love, etc --- all the things we need to negotiate the world fruitfully and independently. In such a situation, which may certainly include childhood traumatic situations, a person brings all they have and know to the situation and over time are emptied or reach the limit of these resources. At the same time one can, and hopefully will, experience a sense of empowerment one knows comes not only from within but from beyond themselves as well. When this happens, when the desert becomes a place of meeting with God as well as of stripping and emptying, such a person continues to live with a fresh courage and sense of meaning and hope. They embrace their own weakness honestly as they humbly and gratefully accept the life which is received as complete gift in such situations.

When I speak of a desert I mean the literal wilder-nesses we know as deserts (the Thebaid, Scetes, Mojave, Sonoran, Sahara, etc), but I also mean any extended situation which demands or forces a person to plumb the depths of their own personal resources --- courage, intelligence, creativity, sense of security, personal gifts and talents, sense of self, faith, hope, love, etc --- all the things we need to negotiate the world fruitfully and independently. In such a situation, which may certainly include childhood traumatic situations, a person brings all they have and know to the situation and over time are emptied or reach the limit of these resources. At the same time one can, and hopefully will, experience a sense of empowerment one knows comes not only from within but from beyond themselves as well. When this happens, when the desert becomes a place of meeting with God as well as of stripping and emptying, such a person continues to live with a fresh courage and sense of meaning and hope. They embrace their own weakness honestly as they humbly and gratefully accept the life which is received as complete gift in such situations. All kinds of situations result in "desert experiences." Chronic illness, bereavement, negligent and abusive family life, bullying, losses of employment and residence, abandonment, divorce, war, imprisonment, insecure identity (orphans, etc), serious poverty, and many others may be classified this way. Typically such experiences distance, separate, and even alienate us from others (e.g., ties with civil society, our normal circle of friends and the rhythms of life we are so used to are disrupted and sometimes lost entirely); too they throw us back upon other resources, and eventually require experiences of transcendence --- the discovery of or tapping into new and greater resources which bring us beyond the place of radical emptiness and helplessness to one of consolation and communion. The ultimate (and only ultimately sufficient) source of transcendence is God and it is the experience of this originating and sustaining One who is Love in Act that transforms our isolation into the communion we know as solitude.

All kinds of situations result in "desert experiences." Chronic illness, bereavement, negligent and abusive family life, bullying, losses of employment and residence, abandonment, divorce, war, imprisonment, insecure identity (orphans, etc), serious poverty, and many others may be classified this way. Typically such experiences distance, separate, and even alienate us from others (e.g., ties with civil society, our normal circle of friends and the rhythms of life we are so used to are disrupted and sometimes lost entirely); too they throw us back upon other resources, and eventually require experiences of transcendence --- the discovery of or tapping into new and greater resources which bring us beyond the place of radical emptiness and helplessness to one of consolation and communion. The ultimate (and only ultimately sufficient) source of transcendence is God and it is the experience of this originating and sustaining One who is Love in Act that transforms our isolation into the communion we know as solitude. Thus, my tendency is to answer your question about the possibility of developing the heart of a hermit without experiences of loss, trauma, or brokenness in the negative. These experiences open us to the Transcendent and, in some unique ways, are necessary for this. Remember that sinfulness itself is an experience of estrangement and brokenness so this too would qualify if one underwent a period of formation where one met one's own sinfulness in a sufficiently radical way. Remember too that the hermit vocation is generally seen as a "second half of life" vocation; the need that one experiences this crucial combination of radical brokenness and similar transcendence and healing is very likely part of the reason behind this bit of common wisdom.

Thus, my tendency is to answer your question about the possibility of developing the heart of a hermit without experiences of loss, trauma, or brokenness in the negative. These experiences open us to the Transcendent and, in some unique ways, are necessary for this. Remember that sinfulness itself is an experience of estrangement and brokenness so this too would qualify if one underwent a period of formation where one met one's own sinfulness in a sufficiently radical way. Remember too that the hermit vocation is generally seen as a "second half of life" vocation; the need that one experiences this crucial combination of radical brokenness and similar transcendence and healing is very likely part of the reason behind this bit of common wisdom. In any case, the heart of a hermit is created when a person living a desert experience also learns to open themselves to God and to live in dependence on God in a more or less solitary context. One need not become a hermit to have the heart of a hermit and not all those with such hearts become hermits in a formal, much less a canonical way. In the book Journeys into Emptiness (cf.,illustration above), the Zen Buddhist Master Dogen, Roman Catholic Monk Thomas Merton, and Depth Psychologist Carl Jung all developed such hearts. Only one lived as a hermit --- though both Dogen and Merton were monks.

As I understand and use the term these are the hearts of persons irrevocably marked by the experience and threat of emptiness as well as by the healing (or relative wholeness) achieved in solitary experiences of transcendence and who are now not only loving individuals but are persons who are comfortable and (often immensely) creative in solitude. They are persons who have experienced in a radical way and even can be said to have "become" the question of meaning and found in the Transcendent the only Answer which truly completes and transforms them. In a Farewell to Arms, Hemingway said it this way, [[The World breaks everyone and then some become strong in the broken places.]] The Apostle Paul said it this way (when applied to human beings generally), "My grace is sufficient for you, my power is perfected in weakness."

As I understand and use the term these are the hearts of persons irrevocably marked by the experience and threat of emptiness as well as by the healing (or relative wholeness) achieved in solitary experiences of transcendence and who are now not only loving individuals but are persons who are comfortable and (often immensely) creative in solitude. They are persons who have experienced in a radical way and even can be said to have "become" the question of meaning and found in the Transcendent the only Answer which truly completes and transforms them. In a Farewell to Arms, Hemingway said it this way, [[The World breaks everyone and then some become strong in the broken places.]] The Apostle Paul said it this way (when applied to human beings generally), "My grace is sufficient for you, my power is perfected in weakness." Hermit hearts are created when, in a radical experience of weakness, need, yearning, and even profound doubt that will mark her for the rest of her life, she is transformed and transfigured by an experience of God's abiding presence. A recognition of the nature of the hermit's heart is what drives my insistence that the Silence of Solitude is the goal and gift (charism) of eremitical life; it is also the basis for the claim that there must be an experience of redemption at the heart of the discernment, profession, and consecration of any canonical hermit. While she in no way denies the importance of others who can and do mediate this very presence in our world, the hermit gives herself to the One who alone can make her whole and holy. She seeks and seeks to witness to the One who has already "found" her in the wilderness and found her in a way that reveals the truth that "God alone is enough" for us.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:05 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: desert spirituality, Heart of a Hermit